Edmund Hooper (c1553–1621): 5 Keyboard Pieces performed on clavichord, Flemish harpsichord and chamber organ by Terence Charlston with ‘Some notes on the clavichord and the virginalists’

First published November 2021

Some notes on the clavichord and the virginalists

The Music

‘Alman’ [in A] Brookes, no. 1800

FVB, p. 329

PIV, no. 15

DPIV, 15

FVBB (1899/1969) ii, [CCXXII] p. 309 Shown

GTV, 12

HPI, 15

SEKM xvi, 7

Clavichord (video) https://youtu.be/kkb-jqB6chk

Flemish harpsichord, 8’ alone (sound file)

Organ (sound file)

Anon. [Edmund Hooper?] 'Coranto' [in A] Brookes, no. 422

FVB, p. 329

FVBB (1899/1969) ii, [CCXXI], p. 308 Shown

This unascribed piece is in the same key as the above ‘Alman’ [in A, Brookes no. 1800] and the two work well as a pair. It has similar harmonic plan to Hooper’s Alman which succeeds it and it could be by him on those grounds. Its juxtapositions of rhythm, via hemiolas and syncopations, represents an amalgam of the galliard and coranto, one as it were growing into the other.

Clavichord (video) https://youtu.be/JnKWzVczcxo

Flemish harpsichord, 8’ + 4’ (sound file)

Organ (sound file)

'An Allmaine' [in d] Brookes, no. 1801

NYp Drexel 5612, p. 164

Edition:

ECCG, 31 (p. 30) Shown

GTV, 14

Clavichord (video) https://youtu.be/ZeH2LLzpyO4

Flemish harpsichord, 8’ with buff stop in bass (sound file)

Organ (sound file)

'Corranto' [in C] Brookes, no. 1802

FVB, p. 331

BEE ii, 13

FVBB (1899/1969) ii, [CCXXII] p. 312–313 Shown

SEKM xvi, 3

Another setting attributed to John Bull (Brookes no. 1183) in Pc Rés. 1185, p. 280 (anon.)

Clavichord (video) https://youtu.be/L6EHWcGSgJ4

Flemish harpsichord, 4’ alone (sound file)

Organ (sound file)

'An Almayn' [in a] Brookes no. 1608 (?Hugh Facy)

NYp Drexel 5612, p.53

ECCG, 9 (p. 12) Shown

Clavichord (video) https://youtu.be/MI9XR4Lo2ok

Flemish harpsichord, 8’ with buff stop to both treble and bass (sound file)

Organ (sound file)

Not included

‘The First Part of the Old Year’ and ‘The Last Part of the Old Year’ (Brookes, nos. 557 and 699) from Parthenia Inviolata, nos. 7 and 8 have not been included. They are given a doubtful attribution to Hooper in Morehen, J. ‘Hooper, Edmund’ Grove Music Online. Retrieved 31 Oct. 2021, from https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000013313.

Abbreviations

|

Printed sources |

|

|

PIV |

Parthenia In-Violata, or Mayden-Musicke for the Virginalls and Bass-viol, selected by Robert Hole (London, c.1625) Online copy of (issued 1614?) https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b4085790-a382-0133-1b36-00505686a51c |

|

Manuscript

sources |

|

|

FVB |

GB-Cfm

32.G.29 (Fitzwilliam Virginal Book) |

|

Drexel 5120 |

US-NYp Drexel 5120 [?ms copy of Parthenia in-violata] |

|

Drexel 5612 |

US-NYp Drexel 5612 |

|

Editions |

|

|

BEE |

Early English Keyboard Music. 2 vols. Ed. Eve Barsham. London: Chester, 1980. |

|

DPIV |

Parthenia In-Violata. Ed. Thurston Dart. New York, 1961 |

|

ECCG |

English Court & Country Dances of the Early Baroque: From MS Drexel 5612. Ed. Hilda Gervers. American Institute of Musicology Hänssler-Verlag, 1982/1998 |

|

FVBB |

The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, ed. J.A. Fuller Maitland and W. Barclay Squire. 2 vols. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1899/ Reprint Dover, rev. Blanche Winogron, 1969 |

|

GTV |

Thirty Virginal Pieces by Various Authors. Ed. Margaret Glyn. London, 1927 |

|

HPI |

Parthenia In-Violata. Selected by Robert Hole. London, 1952 |

|

SEKM xvi |

Twenty-Four Pieces from the Fitwilliam Virginal Book. Early Keyboard Music Series. London: Stainer and Bell, 1958/rev. 1964 |

Some notes on the clavichord and the virginalists – Terence Charlston (2021)

The clavichord was widespread in 16th-century Europe. While clavichords are known to have been widely used in England and Scotland at this time, no instruments of incontrovertible British provenance survive today.[1] The situation is somewhat similar in France where clavichords are known to have been made and played, but none have come down to us.

In this early period, clavichord construction followed a limited number of simple designs across a wide area (later including the new world) and a broad time span of hundreds of years. The consequent lack of identifiable, discrete national or geographical types adds to the difficulties of making secure attributions. Furthermore, the predominance of Germany, Spain, Portugal and Scandinavia as the main centres of clavichord making and playing from the 17th century onwards has overshadowed our appreciation of the clavichord in Britain (and France).

While the surviving historical evidence however suggests that clavichords were widely used in Britain until the 18th century in a variety of keyboard and non-keyboard music, modern players have been slow to explore this rich repertoire on the clavichord, even though its suitability has frequently been noted. To redress the balance a little, I have been working my way through a few of these hitherto unexplored possibilities.[2]

The evidence

Contrary to the traditional view that the clavichord has been little associated with Britain, iconographic and written references from the fifteenth century to the late eighteenth century suggest it was widely known and valued.

The earliest surviving depiction of a clavichord in Britain is the Old Sarum Breviary and Antiphonary, from Ranworth Parish Church, Norfolk, dated about 1400. Also notable are a wooded carved roof boss at St Mary's Church, Shrewsbury (ca. 1440) and the stained-glass image in the Beauchamp Chapel at St Mary's Church, Warwick (1439-47).[3]

In addition to iconographic evidence, many surviving written documents describe clavichords in the contexts of ownership (indicating status and worth), and in performance, including accounts of payments for maintenance and tuning, and as a tool for teaching.

Earliest surviving written evidence of clavichord in England dates from about 1407, and in Scotland 1497, but if eschequier describes a clavichord in much earlier document, then Edward III gave one to John the Good of France, about 1360.[4] Significant references include Lincoln Cathedral (1477), Henry VII (1502 and the inventory of instruments at his death, 1547), Sir Thomas More (c. 1530), an automatic, solar-powered clavichord for James I (1609–10) and a payment to John Hingston for tuning a clavichord in 1660.[5] Regarding its ubiquity in England and particularly the period of the virginalists (1570–1630): see Wardman (2000); in Cambridge 1545-1559 see Knights (2008) and Durham 1569 see Knights (2006). For repertoire suggestions including the virginalists see Adlam (2003), and for a music manuscript dated to the 1680s with pieces specifically allocated to the clavichord ('fitt for the Manichorde') see Hogwood and Brauchli (2003). For further references to the courts in England and in Scotland, 1502-1547, see Boxall (1999) and Mirrey (2003).

Maria Boxall suggests that the clavichord may have come to England from Spain through the visits of Spanish court and their distinguished musicians.[6]

References

Grove Music online (‘Hooper, Edmund’ by John Morehen. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.13313. Published in print: 20 January 2001Published online: 2001)

Derek Adlam, ‘An English Repertoire for a Sixteenth-Century Clavichord’, De Clavicordio VI (2006 Proceedings), pp. 148–156

Edmund Bowles, 'A Checklist of Fifteenth-century Representations of Stringed Keyboard Instruments', Keyboard Instruments: Studies in Keyboard Organology, 1500–1800, ed. Edwin Ripin (Dover 1977), pp. 1–19

Maria Boxall, ‘The monacorde in England and Scotland 1407-1548’ British Clavichord Society Newsletter 14 (June 1999), pp. 15–17

Garry Broughton, ‘In Search of Sir Thomas More’s Clavichord: Part 1’ British Clavichord Society Newsletter 33 (October 2005), pp. 2–6

–––– ––––, ‘An Early 17th-century Solar-powered Clavichord?’ British Clavichord Society Newsletter 64 (February 2016), pp. 12–16

Terence Charlston, Mersenne’s clavichord: music from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century France. [Audio] (2015) DDA 25134, CD booklet.

–––– ––––, ‘Clavichord’, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Historical Performance in Music, Lawson, C., & Stowell, R. (Eds.). (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 136–138.

–––– ––––, ‘Patterns of play: Orlando Gibbons, Simon Lohet and J. S. Bach’s Fugue in E major BWV 878/2. Part ‘I. Clavichord International, 23/2 (November, 2019). pp. 39–48.

–––– ––––, Johann Jacob Froberger, Fantasias, Canzonas, clavichord, audio recording. (2020) DDA 25204, CD booklet.

Gregory Crowell, 'Some Observations on the Clavichord in England and the American Colonies in the Eighteenth Century', Clavichord International 4/2 (November 1999), p. 49

Christopher Hogwood and Bernard Brauchli, ‘The Clavichord in Britain and France: A Selection of Documentary References before 1700’, De Clavicordio VI (2006 Proceedings), pp. 157–184.

Francis Knights, ‘New historic references to the clavichord in Durham’, British Clavichord Society Newsletter 46 (October 2006), pp. 6-9

–––– ––––, ‘The clavichord in Tudor Cambridge’, British Clavichord Society Newsletter 36 (June 2008), pp.3-7

Lynne Mirrey, ‘The Early Clavichord in Scotland’ British Clavichord Society Newsletter 25 (February 2003), pp. 5–8

Judith Wardman, ‘Clavichords in England: more information from Michael Fleming’, British Clavichord Society Newsletter 16 (February 2000), pp. 16–17

The Instruments

Clavichord

Fretted Clavichord by Andreas Hermert (2019) after the instrument No. 2160 of the Musical Instrument Museums, Berlin (Augsburg or Nuremberg around 1700). Pitch: a1 = 466 Hz. Temperament: quarter-comma meantone.

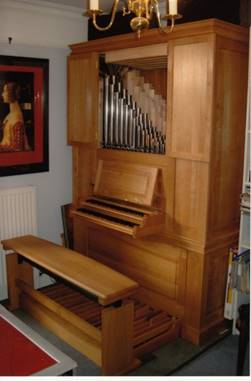

Organ

Two Manual and Pedal Practice Organ by Vincent Woodstock (2002). Upper manual 8’ stopped diapason (wood). Pitch: a1 = 440 Hz. Temperament: quarter-comma meantone.

Harpsichord

Single-manual harpsichord after Ioannes Couchet,